Karl Marx, AI and Heinrich Heine - Poetry Translation

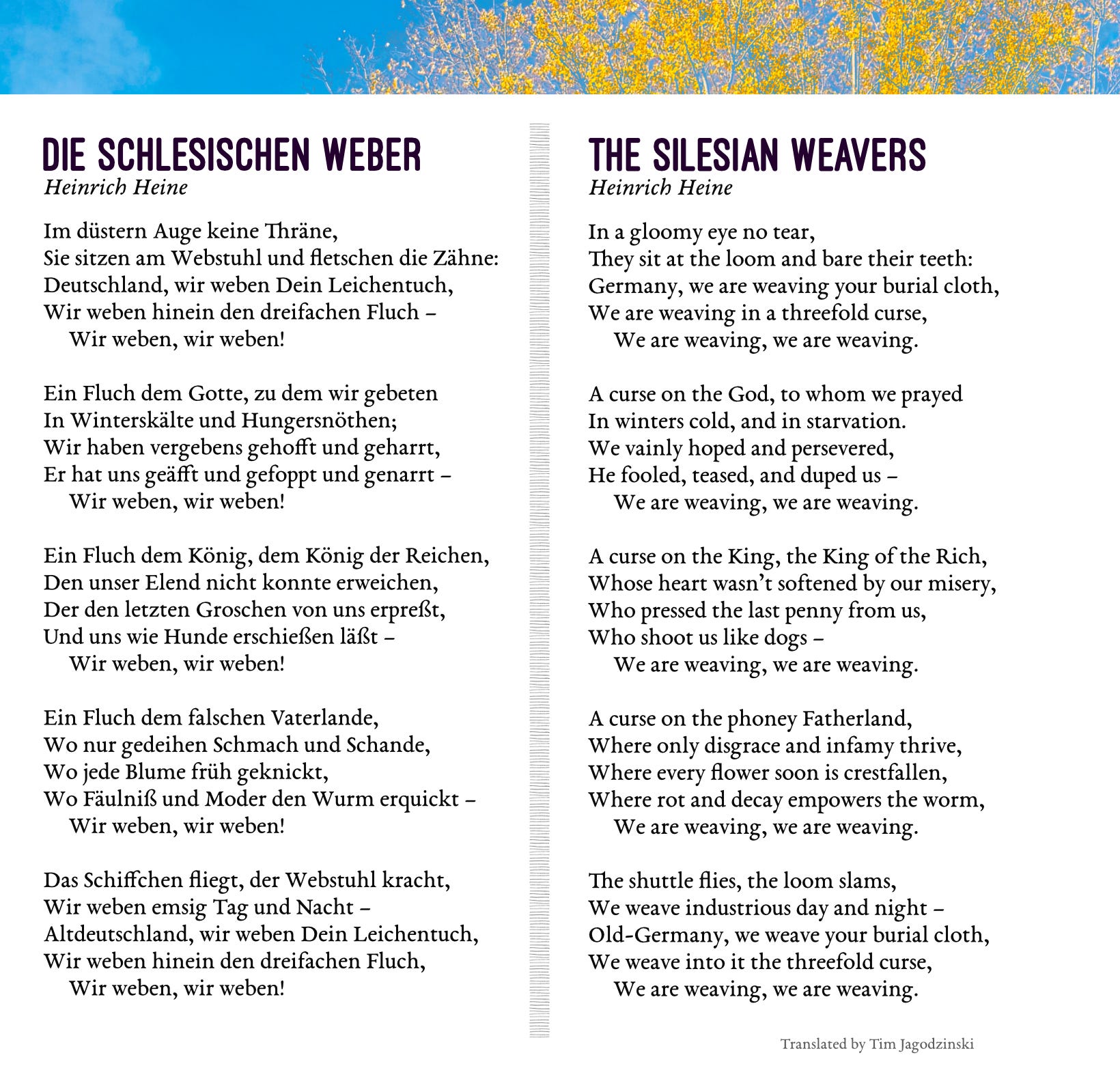

How “The Silesian Weavers” turned Heinrich Heine’s fiery Passion into a weapon again oppression and heartlessness.

A Rebel In Love

Heinrich Heine (from 1797 to 1856) was a person driven by a dichotomy. He was as famous for his vivid poetry about love, as for his poetry directly going against the German government. It’s a bridge not many people have inside of them, but what made this dichotomy work was his passion. The same passion that drove his heart to love drove his mind to fight for freedom and justice.

That also meant that I was torn. Should I highlight his politics, or his romantic aspect? I decided to pick one of his political poems. We already have enough poetry around us about emotions and feelings. I wanted to show you how poetry can be an important tools for politics and how we can connect it to our history.

That it was seen as a weapon by the Germans was clear. Not only did Heine live in voluntary exile in France, where he could publish more freely, his works were routinely censored or outlawed in Germany. In fact, a person got imprisoned in 1846 for reciting “The Silesian Weavers” in public after a royal Prussian judge outlawed it for being rabble-rousing.

The Uprising of the Weavers

Part One

Before we go and read the poem you need some context. As you will see, the language in the poem is very clear and straightforward. The reason is that this is a propaganda piece. It was published in a newspaper controlled by Karl Marx. Its purpose was to tell the people who were suffering who was to blame. It also gave people who were already activists a tool and words to use.

Weaving was a traditional trade that gave many people work as the progress was slow and cloth was needed everywhere. In the early years of industrialisation, automated looms were invented and forced weavers into unemployment. This was made worse by the German government, that had taxes, tolls, and tariffs in place. These extra financial burdens made linen created by hand even less competitive. Even in the face of that, the government would not remove or even reduce these.

This situation is similar to what we see right now happening with AI – but without any welfare state to help. The new looms made cloth cheaper and the society more wealthy, but the weavers had to carry the burden. Like today, new jobs were created, but these were available for the next generation – not the original weavers.

This led to a huge societal rift and was one of the central events leading to the ideas of socialism and the welfare state. The revolt was put down by military and 11 weavers were shot and killed as stanza three picks up.

The Uprising of the Weavers

Part Two

The content of the poem itself is straightforward, but its structure is important because it’s based on the power structure and political situation in Germany in 1844.

The two main pillars of power were God and the King. Praying to God didn’t change the situation, and the King did not care. The critique against both is obvious and also timeless – but what about the “Fatherland”, why was it cursed?

The concept of a Fatherland was quite a novel invention, as national states were not the norm. The Fatherland as a national state was what Germany was going after, after being caught in regionalism for a long time.

The basic idea was to unify Germany as one big nation. This was a political idea that obviously would not help the weavers. It was simply a continuation of the existing system with newfound nationalism at the center to replace God. (This was also around the time when Nietzsche said, that God was dead, we killed him and have to replace him in our lives.)

Heine saw that and despised the growing nationalism and warned against it and what it would do. In fact, the longing for a national state, unification, and the curse of nationalism haunted Germany and Europe for a long time to come. It took two World Wars and a Cold War to achieve Heine’s goal of a free, liberal Germany.

Conclusion

The discussion of a classic German poem took a different perspective today. Poetry is often caught in beauty, love, and nature, but it can be political, it can say something powerful. Don’t be cynical about it; the role of poetry might be smaller these days, but I think a well-constructed poem can still be a powerful tool.

Bonus Content

I could not leave you with one of Heine’s romantic poems, so here it comes. It is also a great fit for the new year.

As we step into the new year, let’s carry Heinrich Heine’s lesson with us: poetry can stir the heart—and rouse a revolution. Have a wonderful 2025!

All the best,

Tim Jagodzinski